Hypothalamic hamartomas and the foundation that supports these patients

In this quarterly issue, Dr. Lorraine Lazar explains in clear English what hypothalamic hamartomas are, what seizures associated to this would look like, as well as diagnostic and treatment issues. At the end of the article, she also included resources for those who have this condition.

What is a hypothalamic hamartoma?

Also known as a hypothalamic hamartoblastoma, a hypothalamic hamartoma (HH) is a tumor-like non-cancerous lump of tissue in the hypothalamus (bottom region of the brain) that develops during fetal life. Already present at birth, it continues to grow in proportion to normal brain growth, but thereafter does not enlarge or spread to other areas of the brain or body. It is not a cancer and it does not metastasize, but its special location in the brain severely disrupts local hypothalamic brain function (an area of the brain responsible for automatic control of hormonal balance, sexual development, hunger, thirst, and temperature) and may interrupt brain pathways travelling through the region which results in seizures.

What are the symptoms associated with hypothalamic hamartomas?

While clinical symptoms can vary tremendously among patients, mild for some while disabling for others, the onset of symptoms typically begins between infancy and childhood. For a minority of patients, symptoms may not be apparent until adulthood. Two sub-types of symptom presentations (phenotypes) occur, including 1) epileptic seizures with potential problems in development, learning, memory, attention, mood or behavior, and 2) 'central precocious puberty' (brain-related early onset puberty) with physical signs of sexual development present as early as age 2 or 3. Both presentations can occur in the same patient, with about 40% of HH-related epilepsy patients having precocious puberty as well. Severe mood and behavioral changes such as minimally-provoked 'rage attacks' may also occur, highly distressing to both patient and parent.

What kind of seizures are caused by hypothalamic hamartomas?

'Gelastic' seizures (derived from the Greek word 'gelos' meaning laughter) are the hallmark type of seizure associated with HH, resembling odd mechanical-like laughter that can occur multiple times a day. As there is nothing funny happening before the seizure, a child typically feels surprised or distressed by the involuntary forced nature of their laughter. These seizures commonly begin in infancy (mean age of onset 10.4 months, 71% by age 1) and may be mistaken for colic or GE reflux. They are less frequent after age 10 but can begin in adulthood. They are typically difficult to control with traditional anti-seizure medications. Other patient's may manifest 'dacrystic' or 'crying' seizures, or may develop other medication-resistant seizures by around age 4-7 including complex partial (staring), absence (staring), atonic (limpness), tonic (stiffening) or tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures.

How is it diagnosed?

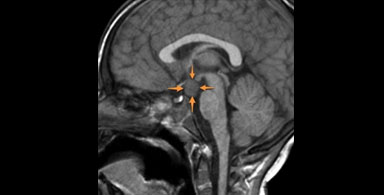

For confirmation that episodes of atypical 'laughing' are seizures, video EEG monitoring is required. Thereafter, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (including coronal T2 fast spin echo/ FSE sequence, with thin cuts through the hypothalamus) is ordered to identify the HH and establish a causative diagnosis. In a minority (< 10%) of patients, there may be additional brain abnormalities. For patients showing signs of early-onset puberty, the HH is commonly attached to the anterior hypothalamus near the pituitary gland, causing abnormal regulation of pituitary hormones. For patients with epileptic seizures, the HH is more commonly attached to the posterior hypothalamus, anatomically disrupting brain pathways travelling between the temporal lobe (responsible for emotion) and frontal lobe (responsible for motor control), resulting in a functional disconnection between 'mirth', the emotional content of laughter, and the motor mechanics of laughter with its complex mouth and pharyngeal movements. For patients with both HH-related epilepsy and precocious puberty, the HH tends to be larger, attached to both the anterior and posterior hypothalamus. With respect to CT imaging, this is typically deferred due to its inadequacy in detecting small lesions like HH and its unnecessary radiation exposure.

What causes it?

The majority (95%) of HH cases are sporadic (random) with no family history of the disorder and appear to reflect a defect in factors that control the fetal development of the hypothalamus. However, there are no known maternal or prenatal external factors that increase the risk of HH. Of the known genetic mutations associated with HH, Pallister-Hall syndrome accounts for the vast majority, associated with a mutation in the GLI3 gene which encodes a regulator protein that turns genes on and off in early fetal development. In addition to the HH, abnormalities seen with Pallister-Hall syndrome include extra fingers and toes, bifid epiglottis, imperforate anus and abnormal facial features. For patients with a hypothalamic hamartoma without additional features of Pallister-Hall syndrome, tissue removed at the time of surgery has been shown to be positive for the GLI3 gene mutation in about 25% of cases. Thus, because this genetic mutation may only be expressed in the HH tissue and nowhere else in the body, peripheral genetic testing via blood or buccal swab for the GLI3 gene mutation is not recommended for the routine care of patients with HH.

How common is it?

Hypothalamic hamartomas are a rare disorder, estimated to occur in about 1 in 200,000 pediatric-aged patients throughout the world, with no preference for world-wide geography or ethnicity. For HH-related epilepsy, there is a slightly increased risk for males compared to females (1.3 to 1). The prevalence of HH with precocious puberty alone is not known.

How is it treated?

For central precocious puberty, a pediatric endocrinologist typically prescribes medication, most commonly gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Treatment of co-morbid short stature may be required as well. Surgery for HH-related precocious puberty is typically not required.

For seizures that do not respond to traditional anti-seizure medications and may be associated with developmental and psychiatric decline, neurosurgical treatment is advised. Among the most effective and immediately beneficial neurosurgical options is 'MRI-guided stereotactic laser thermo-ablation', a minimally invasive neurosurgical procedure involving image-guided placement of thin probes deep into the brain reaching into the HH to heat and destroy it, eliminating its ability to generate seizures. This neurosurgical approach typically yields significantly fewer seizures or even eradicates seizures, particularly when carried out in the younger patient, and may halt developmental or psychiatric deterioration. Overall it yields minimal side effects and relatively short hospital stays. However, alternative neurosurgical approaches may be more appropriate for individual patients depending on lesion size and location, frequency of seizures and other clinical factors.

Can clinicians in NEREG diagnose and treat hypothalamic hamartomas and their seizures?

Yes. With specialized training in the diagnosis and treatment of all pediatric-related epilepsies, NEREG board certified pediatric epileptologists have successfully treated a number of children with HH-related epilepsy. Treatment of these patients requires close collaboration with our team of highly skilled pediatric epilepsy neurosurgeons who utilize the most advanced up-to-date neurosurgical techniques for HH lesion ablation, matching neurosurgical approach with lesion location and patient's clinical course. Our team of neuropsychologists, well versed in the diagnosis and management of the cognitive and behavioral challenges of patients with HH-related epilepsy, focus on alleviating the co-morbid neuro-psychologic symptoms that can be particularly severe, especially in patients with 1) larger HH lesion size, 2) seizures which began at a young age, 3) seizures requiring multiple anti-seizure medications, and 4) seizures which remain frequent. Close collaborations with treating pediatricians, endocrinologists and psychiatrists are maintained as well.

For more information on hypothalamic hamartomas, we recommend the following resources:

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) at rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hypothalamic-hamartoma/

Epilepsy Foundation at epilepsy.com

Hope for Hypothalamic Hamartomas at hopeforhh.org