Feature Article: Autoimmune Epilepsy - the role of inflammation - Epileptologist, Dr. Brenda Wu

What is autoimmune epilepsy?

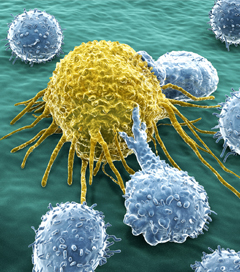

Inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) is frequently activated after CNS damages (infection, ischemic stroke, and traumatic brain injury) and plays an important role in the development of several neurodegenerative disorders, including multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer disease. Inflammation markers have been found in many individuals with epileptic disorders. As epilepsy itself and antiepileptic drugs are reported to alter immune responses, secondary autoimmune disorder inflammation has been proposed to contribute to epileptogenesis (how epilepsy is developed) as well as long-term consequences of seizures (likelihood of drug resistance). Autoimmune epilepsy can be mainly classified as follows:

1) Epilepsy syndromes (e.g. Rasmussen’s encephalitis, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, infantile spasm and Lennox- Gastaut syndrome)

2) Epilepsy associated with other immunologically mediated diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus-SLE, stiff man syndrome, and Hashimoto’s encephalopathy)

3) The more common unselected groups with antibodies to neuronal surface (e.g. antiphospholipid, antinuclear, antiganglioside, and antiglutamic acid decarboxylase).

How long have scientists and doctors known about autoimmune epilepsy?

Autoimmune epilepsy is a new concept introduced in the past few years after growing reports of a strong link between autoimmune disorder and epilepsy surfaced in 2000. These findings include the discovery of serum autoantibodies to neuronal surfaces in individuals with a number of epileptic disorders, pathological findings of chronic inflammation in surgically resected tissues, effectiveness of immunomodulation therapy on refractory epilepsy and numerous non-human biomedical studies.

How is it diagnosed?

There is no standard guideline available for diagnosis of autoimmune epilepsy at present. However, it has been found that the following may indicate the presence of autoimmune epilepsy:

• Clinical history:

1. When the seizure onset is correlated with autoimmune disease exacerbations (multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, Celiac disease and SLE)

2. When seizure onset or breakthrough seizures associated with acute CNS causes damage (head injury, stroke and infections)

3. When epilepsy fails to be controlled after trials of multiple antiepileptic drugs.

4. Childhood febrile convulsions that later develops into temporal lobe epilepsy

• Procedures:

1 Serum autoantibody titers: There are numerous possible neuronal autoantibodies that could indicate inflammation is in play. Just some examples of these are antiphospholipid, antinuclear, antiganglioside, antiglutamic acid decarboxylase, anti-GluR3, and antimitochondrial, etc. A low IgA level may indicate the presence of anti-IgA antibody.

2 Pathological examination of the surgically removed brain tissue from individuals with focal epilepsy that has not responded to other treatments: finding of (scarring) gliosis is consistent with a chronic inflammatory state.

Should all patients be tested for autoimmune epilepsy or are there certain signs that might suggest certain tests are run?

In many cases, autoantibody testing may not be cost-effective. Pathological study is usually not feasible before surgery. Autoimmune epilepsy is mainly diagnosed by clinical history. When immunomodulation therapy is planned autoantibody testing may help to improve the clinical responses.

Are there certain groups that are more likely to present these? Women, children, elderly, certain ethnic groups?

The knowledge of risk factors for autoimmune epilepsy is still very limited. Based on my clinical observation, patients or their first–degree relatives with the following conditions may more commonly present with autoimmune epilepsy: traumatic head injury, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, multiple sclerosis, stroke at young age, asthma, Ig A deficiency, severe environmental allergy, breast cancer, SLE, Hashimoto’s encephalopathy, neuroendocrine disorder (hypothyroidism, pituitary tumor, polycystic ovarian syndrome), lymphoma, hyper-coagulation syndrome and vitamin D deficiency. Possible higher risks are seen in vulnerable populations (elderly, those on chemotherapy, and those after going through an organ transplant) and during periods with significant hormonal changes (adolescence, post-partum, women going through menopause or men around age 50).

How would this type of epilepsy be treated?

Currently, there is no standard guideline available. Traditional antiepileptic medications, VNS and surgical treatments along with immunomodulatory agents such as steroids and ACTH and intravenous immune globulin have the potential to produce significant improvements in refractory epilepsy.

Would the usual epilepsy treatments have an effect on these types of epilepsies (AEDs, surgery, diet, VNS)?

The common epilepsy treatment options may be somewhat effective on autoimmune epilepsy but more evaluations are needed. Certain antiepileptic medications with neuro-protective properties may be effective by blocking the inflammatory process. Diets rich in nutrients improve normal immune-responses to intrinsic and extrinsic stresses. Efficacy of the ketogenic diet is uncertain in such a condition. Surgery may abort focal inflammation but is likely less effective in those with systemic autoimmune disorders. VNS might improve immunomodulation at certain stimulation settings, but the optimal parameters for each individual are not known. Promising antiepileptic medications with immunomodulation properties are expected to be available in the next few years.

Is there anything else a patient might use to treat or improve these types of epilepsy?

Psychotherapies (e.g. stress management), improvement of sleep quality and duration, certain physical activities (Yoga or regular walking daily) or dietary supplements (e.g. omega-3 fatty acid, also proposed Co-Q 10 and vitamin D3) have been reported to accompany improvement of mood and neuro-endocrine regulation and to boost immunity. Conceivably, some patients with autoimmune epilepsy could successfully wean off antiepileptic medications completely once their immune system had recovered to normal. In sum, this is a new and promising field in the world of epilepsy that we hope to continue to understand better in the next few years.